Thought this was an interesting article about Atelier and the “Gothic” style. By the way, head over to Atelier’s site to check out their new spring/summer arrivals.

Labels For More

NEW YORK – American men are tired. Their image, sloppy apes in ill-fitting jeans, white sneakers and baseball hats, has weighed on them for too long. “The ugly Americans” – a term of endearment bestowed on them by the Europeans – has become unbearable. After all, that scathing epithet describes not only their behavior, but also their sartorial (one hesitates to use such a lofty word in connection with denim shirts) fiascoes. Forever optimistic and already conditioned to spending money on such basic needs like big flat-screen TVs and chrome exhaust pipes, American men are striking back.

In 1999, my heart was broken when Barneys, a premier New York department store, dropped such niche designers as Ann Demeulemeester and Raf Simons, sticking with the much safer (read: better selling) Gucci and Prada. Charivari, a chain of cutting-edge menswear boutiques that sold the likes of Comme des Garcons and Yohji Yamamoto, has folded altogether. Yet, less than 10 years later, menswear is back.

The United States accounts for 20 percent of the global luxury market, and menswear is no longer an exception. Despite the astronomical prices charged for high fashion, Barneys menswear business is thriving. Ann Demeulemeester and Raf Simons are back on their racks. Avant-garde designers like Junya Watanabe and Hussein Chalayan have launched menswear lines. And, under the auspices of Hedi Slimane, Dior Homme has become the fashion success story of the decade. A cursory look at DNR, a premier men’s fashion news source, reveals stories of rising profits in menswear, from high street behemoths like H&M to classic luxury shrines like Brioni. Department stores are scrambling to accommodate the growing demand: this January, Bloomingdales unveiled an additional 6,500 square feet devoted to contemporary men’s fashion at their flagship New York store on 59th Street, bringing its total menswear space to 90,000 square feet.

Similar expansion is evident in the fashion media. American newsstands are now overflowing with men’s magazines. The days of heavy-handed GQ dominance are over. From the matronly Vogue to the avant-garde 10, every women’s fashion magazine is launching a men’s counterpart, and these publications actually cover fashion, not beer and pretzels! (Even Men’s Health has begun inserting fashion editorials. Clearly, being stylish is healthy.)

Of course, transitions in tastes happen slowly and awkwardly. As with any enterprise, there is a learning curve that one must master. So it is with fashion (hence, the success of such bad shows like Queer Eye for the Straight Guy). Economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen, who seemed to possess inexhaustible antagonism to anything related to beauty, noted that establishment of taste is a gradual process, which “undergoes a refinement when a sufficiently large wealthy class has developed, who have the leisure for acquiring skill in interpreting the subtler signs of expenditure. ‘Loud’ dress becomes offensive to people of taste, as evincing an undue desire to reach and impress the untrained sensibilities of the vulgar.”

So, where are these “people of taste” in America? Why, in New York City, of course! The creative circles of New York are manifold. Artists and gallery owners, architects and literary agents, musicians and producers constantly seek fashion that manifests their way of life. Given the amount of wealth concentrated in the city, their numbers and their demand constantly grow.

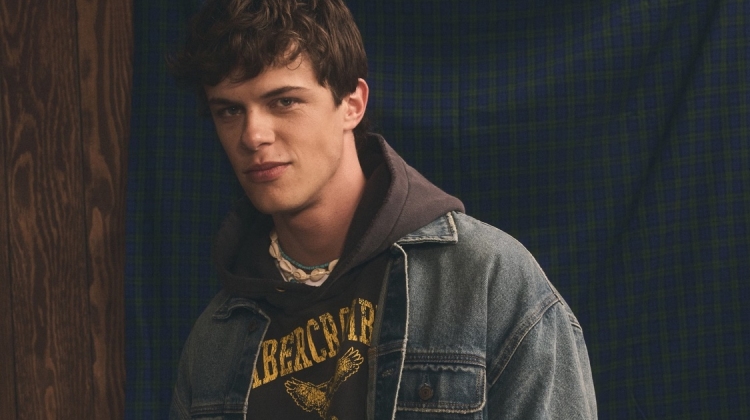

Seeing an opportunity, Karlo Steel, a San Francisco expat, moved to New York to launch a small men’s boutique, Atelier, in 2002. It started out quietly, but soon became a destination for the fashion cognoscenti of New York and beyond. Later this year, the store will move to a space three times its current size.

I read about Atelier before it opened. I would have easily passed over the small magazine blurb, but my eye caught familiar designer names: Raf Simons and Dirk Schonberger. My heart skipped a beat; their clothes were nowhere to be found in New York. The magazine did not provide Atelier’s address, only the neighborhood: SoHo. I searched for the store in vain, until one day I went to the Housing Works Used Book Cafe. The cafe is in a tiny street on the outskirts of SoHo, next to a homeless shelter. This block is one of the last vestiges of the pre-gentrification era, before SoHo was neutered by cheap mass-market stores like H&M and luxury mass-market stores like Louis Vuitton. As I was walking out, I caught a glimpse of an unassuming shop window, framing two mannequins. One glance at the clothes, and I immediately knew this was Atelier.

The boutique itself is small; its four long racks hold about 200 pieces. The walls are painted off-white and covered with mirrors, placed well above eye level. In the middle of the store, there are two display tables. At the far end, a desk, two display cases with jewelry, vintage fashion books, bags and knitwear. The footwear, mostly boots and shoes, stands on the floor. This study in monochrome is a product of Fernando Santangelo, the interior designer behind the Chateau Marmont hotel in Los Angeles (he is currently working on Atelier’s new location). The lighting in the store is dim, and there is always a soundtrack of post-punk and electro-pop playing in the background.

Atelier’s staff wear what they sell, and not because they have to. There is continuity between their lives and their work. Jo-Jo favors Rick Owens and Carol Christian Poell. James is usually in Carpe Diem. Satoru effortlessly mixes Raf Simons with Yohji Yamamoto. Karlo likes to wear Ann Demeulemeester; her clothes sit well on his tall, slim frame. Black is the reigning hue, and the emphasis is on texture and cut rather than on color and ornament. In turn, this attracts a monochrome-clad clientele ranging from young artists, to actors, to rock stars.

‘The suit is dead’

Karlo Steel, a New Orleans native, is serious, soft spoken, and contemplative. Only his dark eyes, set behind horn-rimmed glasses, and an occasional chuckle give away his emotions. And yet his passion shines through his impassive demeanor. He wears his fashion heart on his sleeve. As he unfolds a long gray coat by Austrian designer Carol Christian Poell, he talks about it in his quiet voice. Of course, the explanation must start from afar; Steel is not satisfied with merely describing the garment.

“First of all, let me give some background information. Tailoring for men is slowly dissolving from our lives. The suit is dead. Today, men wear suits only when they have to. Compare that to 1948, when every man wore a suit every day. One of the few people who are infusing a sense of modernity into traditional tailoring is Carol. I am not necessarily talking about designing something new, but breathing a new life into a corpse. He is taking traditional, conservative tailoring and bringing it up to date. There is an element of experimentation that goes into his work. Not all of it is successful, but that’s the price you pay. This is the intersection of what was, and what will be. This is why Carol is important to us – he is the anchor of what we do at Atelier.”

And this is all before Steel even says anything about the coat, the streamlined cut with narrow shoulders and high armholes, the exquisite gray wool, the seams sealed with heat- and water-resistant tape, and the lack of lining that proudly exposes the coat’s construction. Maybe this is one of the reasons why the store does so well.

Would you say that there is higher awareness about fashion among men in America today compared to 10 years ago?

Steel: “Probably. At least it seems like it on the surface. One glance at a newsstand can tell you that. There are many more men’s fashion magazines today – obviously they reflect an interest. But one has to be careful about drawing conclusions. The population has grown, and so has interest in specific things. I was once asked whether men are dressing up more, and I don’t know how to answer that. Answering ‘yes’ would be a flippant response, because I operate in a codified, preaching-to-the-converted environment. The interest has grown, but maybe not enough; when I walk on Broadway, I don’t see it. There are trendies, but they were always there. Maybe there are just more of them.”

The Internet allows for concentration and ease of reach by the media. Maybe an interest in fashion has grown through that? The men’s market is becoming what the women’s market has always been.

“Yes, men’s fashion has certainly become more of a collective conscience phenomenon. However, there is a difference in talking about fashion and consuming fashion. I am interested in the consumer. We are only busy when the cash register rings. Sometimes no one walks in the store, but we send merchandise to a client in Chicago or Los Angeles. The questions don’t count, cash does. After all, it is a business.”

Describe your clientele. What do they do?

“Creative professionals. People who do not have to wear a suit to work. A large percentage of our clientele works in fashion. We also get artists, actors and pop stars.”

You are moving to a much bigger space after being only five years in business. What contributed to your expansion?

“I am lucky to be able to afford the luxury of being in New York. We couldn’t do this in any other city in America. Because we are in New York, we can be as specific as possible. Our expansion is mostly due to more people discovering our store. We are pretty low-key. For the first two years we were called A, which you cannot Google or find in a phonebook.”

Why did you decide to open a store?

“Constantin von Haeften (the co-owner) asked me. I was doing some styling work in San Francisco at the time, and he wanted to open a boutique. I was resistant to the idea at first. I did not think I would be any good at it, and it took some convincing on Constantin’s part. One of the things I kept in the back of my mind when putting the store together was that a store like that was missing in New York. I was surprised that it wasn’t already there in a city of this magnitude.”

So was I, actually. I remember department stores dropping many avant-garde designers.

“There wasn’t anything wrong with the designers, the problem was the stores. A lot of these clothes are very subtle and they require a more informed eye. It’s hard to compete with the flashy offerings on the next rack. A lot of these clothes need to be explained, otherwise the details are easily missed, and the clothes are easily dismissed because of the high price.”

Your store has a particular aesthetic that can be described as dark or gothic. This aesthetic does not seem to come from merely a desire to satisfy a niche, but from something personal. Is this true?

“What I do is deeply personal. I am lucky that a lot of people connect with it. I am really attracted to cities. When I think of cities, I see concrete and graphite, gray, black and white. I never picture myself in a bucolic countryside. I am not against these environments, but whenever I picture myself, it’s urban – there are certain vibrations, textures and feelings that come with that, and that is expressed through the brands I am attracted to. I do not see myself particularly as gothic, although there is a lot of black and distressed clothing in the store. I am kind of romantic, but in a sense that things do not always end well, not in a pastoral sense.”

Some designers you carry, Ann Demeulemeester, Number (N)ine, Rick Owens, are often accused of doing the same thing. However, it seems that what they do comes from the inside and that anything else would be inauthentic.

“This is true with some designers we carry. Yet there are others, particularly from Japan, who tend to imitate. It’s a cultural thing, an idea that imitation is the highest form of flattery. In the avant-garde fashion realm, there is a torch being passed down. In the 1980s the Japanese, Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garcons, began it, their clothes were a novelty; black, asymmetric and deconstructed. They influenced the Belgians, such as Ann Demeulemeester and Martin Margiela, who came in the ’90s. Now, the torch is being passed back to the young Japanese designers, who are looking up to the Belgians. For example, if I see Number (N)ine, I think Ann Demeulemeester. The influence is there, and he wouldn’t deny it, but he does it in his own way. The cognoscenti can read the references, but there are differences when you put the garments side by side. Andy Warhol once said that you are allowed to copy as long as you change two things. Sometimes you have to start somewhere, and through imitation you can come to your own ideas.”

These designers represent two generations. One came in the late ’90s, and the other fairly recently. They appeal to younger clients. And then you have Yohji Yamamoto, an important designer, but from an older generation. Was the decision to carry him a gamble?

“Yes. We were offered to carry Yamamoto; an opportunity I could not pass up. It was an emotional decision on my part. Growing up in the late ’70s, I went searching for what I wanted to wear in my life. I knew I wasn’t getting it from GQ or Vogue. It wasn’t reflecting the kind of music I listened to, the kind of movies I watched. Then I came across new magazines like Face, Blitz, and I.D., English magazines. They were more about style rather than fashion; they were not about what you were wearing, but how you were wearing it, and how the clothes were connected with other cultural phenomena.

“The two names that stuck out were Comme des Garcons and Yohji Yamamoto. Yohji is someone who I’ve always held dearly to my heart. I appreciate his influence and integrity. When we were offered the collection, I knew that Yohji was in some areas out of sync with what we do, but he also started it all. It’s not easy, but I can see how it is causing some people to reconsider Yohji. Of course, I always try to buy what works with the shop. You do not necessarily have to subscribe to the designer’s point of view.”

There is also the other side of the shop: Carpe Diem, Carol Christian Poell and Label Under Construction. These are not “designers” in the traditional sense; they consider themselves artisans. What attracted you to them?

“It was something I felt drawn to. I can appreciate their point of view and connect with their aesthetic. It’s hard to talk about all of them together, because they are all different.”

What unites them is the handmade approach of a craftsman. Does that play a big part in this attraction?

“Yes, and that is something I am aiming to explore further. In the world of instant access and obvious commercial desires, it is nice to find something that does not keep those things at the forefront. The garment is at the forefront, and I respect that. Having designers that show off the standard semi-annual fashion week schedule is inconvenient for me as a buyer, and I wouldn’t do it for something that wasn’t worthwhile.”

Talking about $5,000 leather jackets and avoiding commercialism is problematic. People look at price tags, but not necessarily at the garments.

“We live in a culture where people know the price of everything, but the value of nothing. I suppose it’s a sign of the times, because everything is popular and instant. It is refreshing to find these designers in such a climate. I do not want to compare what they do with art, but there are parallels. Art by its very nature is anti- populist. And yes, it is very expensive. I wish it weren’t, but we also have a weak currency, and a lot of these designers come out of Europe, especially Italy. It is an interesting topic in itself. Italy is very ‘Italian’ in regard to fashion. There are some very big names in Italy that push a certain flashy, gaudy aesthetic, with a small underground school working against that. For every culture there is a counter-culture. If you grew up on a diet of shiny gold, you might want some dull leather.”

Where do you see yourself in this business in the future?

“I am hoping that things will continue the way they are, but just a little bit bigger. I would be happy to continue what I do, and that’s the most important thing in my life.”

Eugene Rabkin teaches critical writing at Parsons the New School for Design in New York City.